During the second world war, when Kinji Fukasaku was in his early teens, he and his classmates worked in a munitions factory. The factory was routinely bombed, and in the aftermath the survivors were instructed to clean up the corpses. Evidently, such an experience continued to exert a profound effect on Fukasaku. In his 61st film, a group of students are taken to an island where they are given a weapon at random and instructed to kill one another. For Fukasaku, the central concept of self-preservation among a group of children during extreme circumstances recalled his terrible service in the munitions factory. It was to be his final film.

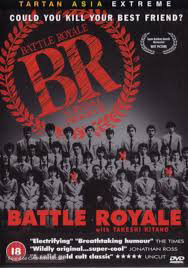

At the time of its release – the year 2000 – Battle Royale caused uproar in Japan. It was debated by parliament, who saw it as a tacit indictment of their competitive national education system, faded martial pride and its increasingly disenchanted youth. Admittedly, to Western audiences, Battle Royale feels like part of a particular strand of dystopian science fiction that began in the Seventies with Rollerball and Logan’s Run, and continued on further into this century with The Hunger Games. Elsewhere, its antecedents include William Golding’s novel Lord Of The Flies.

The film’s timing, too, was relevant. The turn of the century was rife with a certain type of violently apocalyptic cinema: from The Blair Witch Project to The Ninth Gate, Requiem For a Dream or American Psycho. Even The Virgin Suicides found darkness in America’s suburban heartland. Elsewhere, Quentin Tarantino’s movies favoured the kind of stylized violence Fukasaku deployed in Battle Royale – where kids in school uniforms sported sub-machines or wielded machetes. Fukasaku only filmed one scene of the sequel before sadly passing away; his son Fenta continued filming though Battle Royale 2: Requiem has none of the pathos or originality of its predecessor.

Michael Bonner