in-store offers

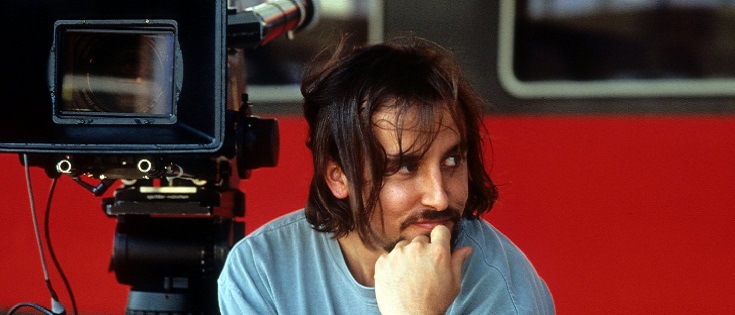

richard linklater

5 of the best

“From Slacker, to Dazed & Confused then on to Before Sunrise; the range of Linklater’s early films defy categorisation”

Dazed And Confused (1993)

Although Slacker was Linklater’s first film, Dazed & Confused has over time become perceived as a more authentic representation of the filmmaker’s early vision. Released in 1991, Slacker was a brilliant, lo-fi tribute to the freaks and geeks in Linklater’s hometown of Austin, Texas; along with Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies and Videotape it became synonymous with a new strain of American indie cinema. But with Dazed & Confused – released two years later – Linklater not only raised the bar on himself, he also established his working MO – that is, never to allow himself to become boxed into any one scene. From Slacker, to Dazed & Confused then on to Before Sunrise; the range of Linklater’s early films defy categorisation.

Much of the joy of Dazed & Confused lies with the performances – conversational, easy-going, affable, traits we can find in other Linklater films. These are people who will happily chat over beer or a joint about music, philosophy or other matters of personal interest, unfussed by the needs of dramatic storytelling. Linklater’s films are digressive, yes; but never aimless. That Dazed & Confused starred a cast of fresh-faced unknowns – including Matthew McConaughey, Ben Affleck and Milla Jovovich – has done it no harm retrospectively. But from the perspective of Linklater’s early catalogue, it’s an artistic leap on from his debut. Set across the last day of class at the fictional Texas’ Lee High School, the film was different in many key respects from other entries in the coming-of-age high school films. Drawn from Linklater’s own memories of high school circa 1976, Dazed & Confused was a complex, personal reflection on adolescence rather than simply a nostalgic frat boy comedy. He revisited similar territory with 2016’s Everybody Wants Some!!!; more buoyant high school high jinks.

Before Sunrise (1995)

The plot for Linklater’s third film was simple enough. An American man and a French woman, both in their early 20s, meet on a train heading across Europe. They alight in Vienna, where they amble around the city for 14 hours, talking. Yet from such a brief storyline, two of the filmmakers most enduring characters emerged: Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy). Although this film took place in 1995, their romance would carry on across another three decades: in 2004’s Before Sunset and again in 2013’s Before Midnight. In each of these three wonderful films, all Linklater’s protagonists did, essentially, was talk to one another in some quite nice overseas locations. But really, the point was that their very real-lifeness was a valuable commodity. In this first film, we encounter an honest but affectionate portrait of a budding romance which is nevertheless infused with the melancholia that both parties know their time together is limited. But truthfully, Before Sunset is the best of the three: set 10 years later it seizes on the regret they feel over the life they could have had together and the teasing romantic notion that their story together isn’t over yet. Taken altogether, the willingness of Linklater, Hawke and Delpy to let the characters develop over 18 makes the Before… trilogy the most genuine romance in movie history.

A Scanner Darkly (2006)

In 2001, Linklater experimented with a relatively new animation technique called rotoscoping. Essentially, this involved filming his actors on digital video and drawn lines and colours on each frame afterwards. It suited the film, called Waking Life, well; this was a surreal set-up involving a continuously looping dream. Linklater revisited rotoscoping five years later for another similarly trippy joint: a Philip K Dick adaptation, A Scanner Darkly. Here was a film that represented accurately the author’s mind-blowing vision of a drug-addled, paranoid and politically unstable world via the medium of animation. Set, in the tradition of all good science fiction, “seven years from now”, A Scanner Darkly found Keanu Reeves, Robert Downey Jr, Woody Harrelson and Winona Ryder adrift in a whacked-out interzone; opaque, occluded and critically alienated from one another and from themselves. Linklater has a funny scene in which his characters have a pointless argument about a bicycle: one of the rare moments where they are discussing something other than drugs. Reeves plays Bob Arctor, an undercover cop investigating a hyper-addictive new drug called Substance D (for Death, of course); in a moment indicative of the film’s Kafkaesque vibes, Arctor finds himself in some confusion when he is assigned to spy on himself. So it goes. But really with A Scanner Darkly, Linklater demonstrated once again his remarkable versatility as a filmmaker and a determination to do something bold, to push himself in a different direction. The result is startling and engrossing; a trip inside a very different sort of matrix.

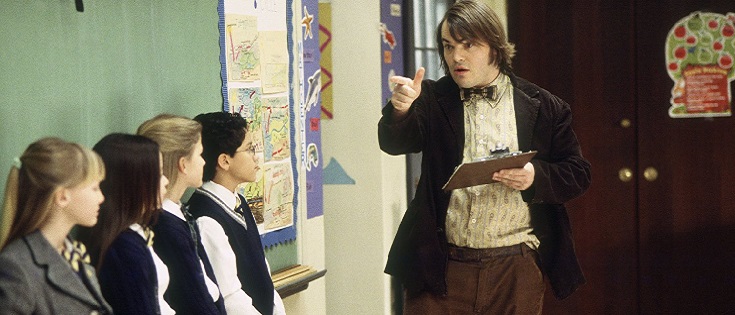

School of Rock (2003)

In many respects, Linklater’s most successful film is also the film that most successfully found a broad national audience for Linklater’s slacker iconoclasm. School Of Rock came from the minds of two leftfield filmmakers – Linklater and Mike White – and met somewhere in the middle as a commercial enterprise, now a West End musical. The film follows the fortunes – or mostly lack thereof – of Jack Black’s Dewey Finn, a failed guitarist impersonating a substitute teacher for reasons of dramatic necessity. The film is about his attempts to rally a group of precocious 5th grade school kids to form a band. Here, and later in Bernie, Linklater gets the best from Jack Black, whose disheveled Tenacious D persona is given rare focus. In cinemas at the same time as the last Lord Of The Rings film and Love Actually, School Of Rock proved remarkably durable: taking nearly $80 million on a reported $20 million budget. Much of that, of course, lies with the crossover appeal of Black performing in a tailor-made role – but critically it is important to give credit to Linklater and White’s impressive film, which straddled generations – a likeable, sweet-natured family film at heart, despite the power chords and stage-diving. Music fans may take some pleasure in learning that Black himself sent each of the three surviving members of Led Zeppelin a videotaped request to allow Linklater to use “Immigrant Song” on the soundtrack. They agreed; a first. All hail the awesome power of rock!

Boyhood (2014)

Shot in 39 says across a 12 year period, Boyhood is certainly Linklater’s most accomplished experiment yet. What partly makes Boyhood such an achievement are the mind-boggling logistics of the undertaking. The time transitions are seamless, the details shift fluidly, the passing of the years marked by clothes, hair, music, mobile phone technology. And of course the principals themselves, who quite literally transform in front of us: Ellar Coltrane as Mason, Lorelei Linklater as his elder sister Samantha, Patricia Arquette as their single mother Olivia and their father Mason Sr (Ethan Hawke), who drifts in and out of their lives.

Olivia moves her children from town to town around Texas. Much of the film’s narrative is concerned with the decisions she makes – the men who begin with so much promise but who solidify over time into something else – and the impact these have on Mason and Samantha. But Linklater avoids making judgments and steers clear from dramatic set pieces, while characters that play prominent roles in Mason’s life vanish as we jump forward in time. Linklater’s concern is how these challenges ultimately shape Mason and his family. There are few moments that feel conspicuously plot-driven; the vibe is natural and free-flowing.

One of the most resonant scenes – and there are many – occurs quite early on. Mason and his father are crashed out on couches at Mason Sr’s, Hogwarts still fresh in the young boy’s mind. “Dad,” he says, “there’s no real magic in the world, right? Right this second, there’s like no elves in the world?” Mason Sr replies: “No, technically. No elves.”

Taken cumulatively, these moments contain the movie’s magic.

Michael Bonner