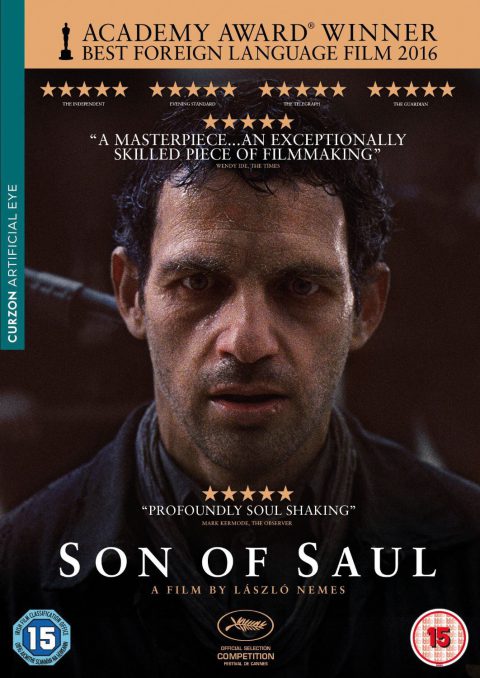

The lengths to which a person will go to survive – the attended moral consequences and their burden – are very much on the mind of filmmaker László Nemes. In Son Of Soul, he focuses on Saul Auslander (played by Hungarian actor Geza Röhrig), a Hungarian Jew incarcerated in the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp in 1944. As a member of the Sonderkommando, Saul has been given a stay of execution in order to help manage the daily business of leading new inmates into the gas chambers and assist with the grisly clean-up operation afterwards.

It is here, inside the chambers, that Nemes’ story begins when Saul believes he has found his son. Subsequently, he goes to perilous efforts to bury the boy’s corpse, hunting through the madness of the camp for a rabbi to help and striking deals with fellow inmates using valuables removed from the dead as currency.

It goes without saying, Son Of Saul is a stark and uncompromising film – more so, perhaps, because Nemes deliberately never softens his gaze. Unlike, say, Schindler’s List or The Pianist – films that dealt with similar subject matter – there is no emotional catharsis here. It is relevant that Nemes worked as an assistant for Béla Tarr, the formidable Hungarian filmmaker whose own ascetic sensibilities are reflected in his protégé’s debut.

Ultimately, though, Son Of Saul is not a film that offers answers. We never know why Saul has chosen to work as a Sonderkommando – an unpleasant, nightmarish task – nor whether the boy really is his son. Making his debut, Röhrig is exceptional – Saul seems to sleepwalk through the horrors around him, as if all normal human emotion and behaviour has been burned away in this horrendous, hellish place. Both he and Nemes should be admired: they have created a forceful and unsettling investigation into the intimate mechanics of mass murder.